Lucian Freud’s etchings have a unique way of paying attention to their subjects.

Sebastian Smee

Lucian Freud, Etchings 1982-2000 at Rex Irwin Art Dealer. Sydney

I wanted to hide so that I could get busy at my real work, which was a sort of wooing of distant part of myself.

Alice Munro Miles City, Montana

So much about daily life these days breaks us up, disperses and jumble our hard-won yet constantly shifting connections to the world. It becomes harder and harder to shore up those connections by, for instance, just sitting and looking; attending to something.

There is a difference of course, between “paying attention” in the way one has to when driving a a car or studying for an exam, and the more diffuse, fluid and supple business of “attending” to someone. It’s this kind of attention, I believe that Jose Ortega y Gasset had in mind when he said “love is a phenomenon of attention”.

Lucian Freud’s work, I often think, is like a natural extension of some true, yet awkward form of love, an echo of the unique rhythms of a certain mode of paying attention to people. It is a very odd, idiosyncratic mode, you sometimes feel but it’s tremendously generous and responsive, too.

Freud’s work has an unironic, foursquare integrity that feels in many ways unique to modern art. In the end, there is something cherishingly irreducible about it. His work has the same mysterious resistance to analysis and expectation that a mature person has.

A show of 43 etching by Freud at Rex Irwin Art Dealer, Woollahra, gives Australian audiences an unprecedented opportunity to see this increasingly important aspect of his output. (There was an exhibition of his paintings at the Art Gallery of NSW in 1992-93.) Forty three amounts to a very good representation: even though Freud is 78, he has made only 61 separate etchings (the editions average about 30).

For 34 years he made none at all: he had come to believe that his celebrated drawing skills, which veered towards the fussily exact, were hampering his expression through paint. He resumed etching in 1982, prompted by the looming publication of Lawrence Gowings’s monograph on him. For a limited first printing to the book he made a total of 15 etchings in one year, and since then he has made only four or five a year.

Etchings are made by drawing with a needle onto a metal plate covered in a layer of acid-resistant coating. The needle onto a metal plate covered in a layer of acid-resistant coating. The needle exposes the metal beneath, so that when the plate is immersed in an acid bath, the acid bites into the exposed lines. A print is then made from the design left on the plate.

The method, as you can imagine, is quite suited to a fussy precision, to working on a miniature scale, and to stippling, cross-hatching and dotted lines – in short, to a style of drawing Fred had already won considerable renown for early in his career. What is astonishing about the etching style he has developed since 1982 is that he has completely reinvented the medium, making it seem like a natural extension of his painting, with its sense of fleshy volumes, stresses, slippages and muffled contours, composed as a whole from the inside out, As the Art Gallery of NSW curator of special exhibitions, Terence Maloon, notes in an essay accompanying the Rex Iwin show: “Because there is no stable, consistent visual code underpinning a (Freud) picture, he must slightly reinvent his visual language for each new etching. As a consequence, the images which emerge retain a precious quota of awkwardness and strangeness”.

This has always been the case with Freud. Even in these late etchings – and despite their surprising softness of contour – he has retained just a little of the fierce regard (verging on deed oddity) common to Northern European portraiture through the centuries and to Freud’s on early work. Behind it, one feels, is a prickliness of intelligence adept at “editing out” things that don’t interest him.

Freud was born in 1922 if Austrian-Jewish descent (his grandfather was Sigmund Freud). He grew up in Berlin in a moderately affluent household but in 1933 – the year Hitler became chancellor of Germany – his family moved to England.

He went to a progressive school and took up horse riding – his earliest extant artwork is a sandstone carving of a three-legged horse. This won him a place at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, which was run by an artist named Cedric Morris who specialised – as Freud would do later – in portraits often described as “blunt” and “honest”. In 1941, Freud ran away to Liverpool and joined the merchant navy. A year or so later he was invalided out, and returned to art school – this time Goldsmith’s College. From this point on, he gathered a reputation as a distinctive artist of increasing merit.

There weas a childish quality of fancy in many of his early works – although this fancy did not exclude the often wilful perversity of childish whims. They were stiff and weirdly proportioned; one imagines the artist drawing with his tongue poking out in unselfconscious determination but with a cold glint of wickedness in his eyes.

These days Freud is renowned as an artist of almost hermetic isolation (he has his few friends’ phone numbers: they don’t have his). He told the critic John Russel: “My work is purely autobiographical. It is about myself and my surrounds. It is an attempt at a record. I work from the people that interest me and that I care about, in rooms that I live and know.”

But there is clearly a powerful sociable streak in Freud, too – how else could he spend so much time (up to 80 hours for each painting) entertaining the many and various models who sit for him?

“One of the ways I could get them to sit was by involving them,” he has explained. The painting was always done very much with their co-operation.”

“Co-operation” perhaps oversimplifies it a bit. There is always a tension between inexperienced sitters and the artists who depict them – a tension Freud has said is lost in the photographic portraiture, where the interaction is more or less instantaneous and arbitrary. In Freud’s etchings, which are infused with an extraordinary sense of duration, the sitter retains a certain capacity for self-censorship; she (or he) has some control over the extent to which she wants to engage with, or reveal herself to, the artist. This felt interaction makes the resulting artwork so much more compelling.

One of my favorite stories about Freud’s relationships with his sitters cropped up in an interview Freud did with William Feaver for the Observer two years ago. He was asked about one of his young (clothed) subjects, Louisa, a girl doing her A-Levels.

Feaver commented: she looks self-possessed.” Freud replied: “And is. She told me about this boy that she liked and the fight they had and how he’d been in Australia for two years and has just come back. And her mother told me that when Louisa told him about the painting, he said, ‘What a shame; I thought that was the only chance I’d have of seeing you naked.’”

When Freud’s subjects do take their clothes off for him, it is almost always the first time they have done so for an artist. “I don’t use professional models,” he told Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, “because they have been stared at so much they have grown another skin. When they take their clothes off, they take their clothes off, they are not naked; their skin has become another form of clothing.”

Nakedness, he has said “deepens the transaction” between himself and his sitters. In many of my own favourite Freuds, however, I suspect the transaction has been fairly one-sided because they are of people sleeping. In this show, I have two favourites: Man Resting, 1988, which shows a bulb-nosed man asleep etched against an empty white ground. His head and bunched shoulder are all we can see; they extend from the left hand side of the frame into a void of white paper. It is an image of deep but babyishly awkward repose – as poetically out-of-place and yet restful as a ruin in a rolling field.

The other, Woman with an Arm Tattoo, 1996, is of Sue Tilley, a very fat woman who sat for some of Freud’s most memorable recent paintings. Again, she is asleep, but in a position we can’t quite make out. The perspective and vantage point are made ambiguous by Freud’s omission of whatever it is she is sitting or lying on.

Her nose is squashed by her hand, and her whole face expresses the endearing human awkwardness of being a conglomeration of flesh and skin, all of it weighed down by gravity, surging with fluids, pockmarked by time. Just thinking about it makes one tired.

Published with the permission of the author.

© Sebastian Smee

Further readings:

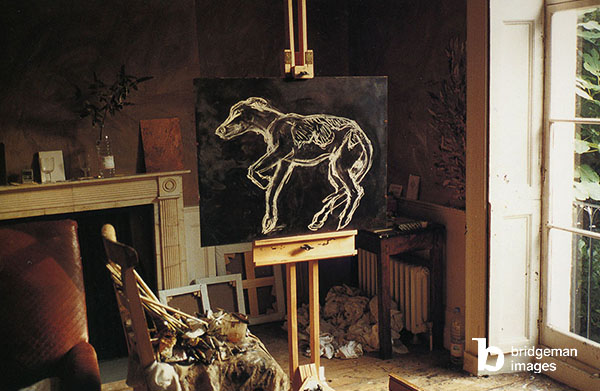

Lucian Freud: Beholding the Animal: Unflinching Truth